Feature

How We Got Started

By Jake Seaton, CEO · September 01, 2020

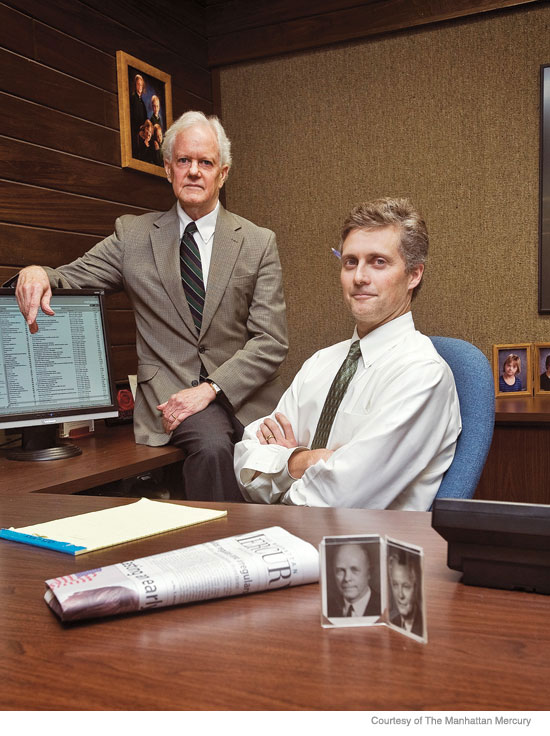

Hi there — my name is Jake Seaton. I’m from Manhattan, Kansas, fondly known as "The Little Apple." The local newspaper there is called The Manhattan Mercury, and it has been owned and operated by my family for the past five generations.

Growing up in Manhattan, I worked as a paperboy and then a reporter at The Mercury. Watching my father and grandfather work together, I developed a deep appreciation for the news business, as well as an understanding of the challenges it now faces.

As the internet disrupted the news and media industry, the Mercury's profit margins plummeted. Google, Facebook and Craigslist largely rendered the newspaper advertising model obsolete. I enrolled at Harvard College knowing that I wanted to help my family's business navigate these transformations — but I wasn't sure how.

In college, I chose to study computer science and journalism because I hoped to learn the skills I would need to help my family business survive. I fell in love with building software and joined a team of smart folks starting a company called Quorum Analytics, which aimed to improve the legislative process by using all of the data available on the internet.

I wound up dropping out of Harvard — at least temporarily — to help get that company on its feet. I and about five others wrote code in a house in northwest Washington, DC while our sales team trotted up and down K-Street.

After two years, the company had grown to about 50 employees and moved into a fancy office downtown. To some of us who had dropped out of college to see if this was possible, there was a feeling that we'd accomplished what we came there do to. For me, at least, there was still something missing.

You see, in my family, being in the newspaper business was about more than selling advertisements. It was about asking hard questions, telling great stories, and participating in a process that is fundamental to American Democracy.

My great great uncle, Fred Seaton, served as Secretary of the Interior for President Dwight D. Eisenhower where he brought Alaska and Hawaii into the union. His father, Faye, purchased The Manhattan Mercury and eventually handed it off to Fred's Brother, RM.

My grandfather, Edward Seaton, was the president of the Inter-American Press Association (now the News Leaders Association), has chaired the Pulitzer Prize committee, and is credited with spearheading the Declaration of Chapultepec, for which he rounded up Latin American heads of state like Fidel Castro and persuaded them to commit to supporting freedom of the press in the Western Hemisphere.

For my grandfather's generation, the persecution of journalists was among the biggest challenges the news businesses needed to overcome. For my generation, that challenge is the internet, which is why I wanted to spend my career helping my family's business grapple with the digital transition.

What I came to love about building software is that you can solve a problem for one person and then instantly scale that solution to every other person in the world who has the same problem. We did this at Quorum for public affairs professionals, and the business grew from a dorm room to an international company with blazing speed.

As I was leaving Quorum I began reaching out to members of the media world that I admired in Washington, DC. Marty Baron had worked with my grandfather, so I started by just asking him to get coffee.

He said yes, which gave me the confidence to send a cold email to David Chavern, the CEO of the News Media Alliance — essentially the head lobbyist for newspapers in America. I explained that I was a young computer scientist with a passion for the future of news, and asked where he saw opportunities for me to make an impact in the industry. His answer surprised me.

He essentially said that if someone like me didn't do something about public notices, a lot of newspapers were going to go out of business.

I had never heard of public notices before, so I went back to Harvard and spent the next two years taking every journalism and media course I could get into, all the while researching public notices.

I wrote a long-form investigative piece in Jill Abramson's Journalism Seminar and an Op-Ed in Nancy Gibbs' course at the Kennedy school. I wrote a program, that, similar to Quorum, would go out and collect every public notice it could find and put them into one central database that I could analyze. I started talking to the customers of my family's company, the government officials that placed notices and the executives of the press associations that fought to defend their continued existence.

Inspired to once again solve a problem in a scalable way, I wrote about 50,000 lines of code to develop a prototype that I called e-notice, a software product that I thought might improve this system in such a way that it could remain a disclosure mechanism for government process and a revenue stream to support local journalism.

I put that prototype in front of anyone who would give me the time of day — from my grandfather, to the president of Gannett, to the Kansas Press Association, who nearly leapt out of their seats with excitement when they saw the opportunity it could provide for them and their member newspapers.

During my final semester at college, I hardly attended class, but worked day and night to assemble the resources to take a serious crack at solving this problem. I banged down the doors of the folks who had dropped out of Harvard with me to start Quorum, as well as some new friends I'd made along the way.

After graduating, we returned from Cambridge, Massachusetts to Manhattan Kansas, where we lived in my mother's basement and worked out of the extra conference room of The Manhattan Mercury. We sat right next to the staff member in charge of public notices.

By the end of the summer, we had a working prototype. We went on to sign a formal partnership with the Kansas Press Association to work with them to roll it out to every single newspaper in Kansas.

We're well on our way. Since the start of 2020, the usage of our product has grown rapidly — ten times over since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. We signed partnerships agreements with two more states and moved the company to Washington, DC, where we could take a nation-wide approach to solve this problem.

We renamed the company "Column," which better represents our mission of improving the utility of public interest information and supporting the distribution of that information by journalists that serve their communities.

Column isn’t perfect yet. We are constantly innovating, iterating, changing, tweaking and improving our understanding of the problem we aim to solve. As we introduce Column to more communities around the country, we look forward to the journey ahead, and we expect it to be full of surprises and hard problems. In fact, we hope it will be, because we believe that the hardest problems are the ones most worth solving.

© 2020 Column, PBC. All rights reserved.